Colette Sadler participă în cadrul ediției #8 a eXplore dance festival cu spectacolele I not I și We are the monsters (performance și workshop)

Andreea Căpitănescu: Locuiești și lucrezi în Berlin, dar ai studiat dansul în Marea Britanie. În ceea ce privește estetica sau tendințele din dansul contemporan, au existat întotdeauna discuții despre cât de diferite sunt cele două scene de dans – cea englezească și cea germană. Care sunt diferențele dintre cele două după părerea ta ?

Colette Sadler: Cred că diferențele dintre cele două piețe de dans sau în general dintre piețele europene se reduc la o anumită definiție sau noțiune a ceea ce înseamnă dansul. Curentul conceptualist care a marcat dansul în anii ’90 nu a atins sau nu a avut un impact asupra scenei de dans britanice ca în restul Europei. Marea Britanie a avut propriile tradiții în balet și dans modern, originând din școli precum Școala de Dans Contemporan din Londra (London Contemporary School of Dance), care au fost influențate major de dansul american modern și postmodern. Scena de dans britanică în general, așa cum o percep eu (de notat, e doar o generalizare), este încă puternic influențată de un anumit tip de estetică raportată la virtuozitate și frumos.

În Marea Britanie, piața de dans este strâns legată de finanțare și criterii precum un public dezvoltat, numărul de bilete vândute, nivelul de angajament social etc. Această situație este similară celei din Berlin, dar finanțatorii din Berlin nu vor întreba niciodată de numărul publicului și angajarea socială. În acest sens, arta și potențialul său de impact social sunt înțelese diferit. Există, în mod natural, diferite piețe de dans în Marea Britanie, dar ar fi destul de dificil să prezint de exemplu munca pe care o fac majorității sau principalelor scene britanice de dans; deși, în Scoția, Work-Room din Glasgow inițiază un proiect prin care încearcă să prezinte diferite tipuri de lucrări în restul țării. De fapt, după o vreme, scenele au cerut lucrări noi. Deci există o mare schimbare de strategie. Locațiile britanice suferă o mai mare presiune financiară în ziua de astăzi, astfel încât există o nevoie ca sălile să prezinte spectacole mai comerciale. Poate că teatrul este în competiție cu televiziunea într-un mod în care nu se întâmplă în Europa.

Am auzit spunându-se că publicul britanic are nevoie sau se așteaptă la o narațiune. Nu cred că este cazul, însă este adevărat că avem o lungă tradiție în teatrul în care predomină cuvântul rostit. Țări ca Franța, spre exemplu, descoperă că le este mai ușor din punct de vedere cultural să se confrunte cu un teatru și dans strâns legate de cultura imaginii și a fotografiei.

AC: Teoria practicii fizice? Ce anume te inspiră cel mai mult în construirea unui nou spectacol?

CS: Pentru că am petrecut mulți ani lucrând ca dansator și mi-am început pregătirea în dans de mică, am dansat aproape toată viața. Munca de coregraf decurge, astfel, direct dintr-o dorință intuitivă de a mă mișca și înțelege lumea în acei termeni, mai degrabă decât dintr-o simplă teorie. Cu toate astea, am căutat întotdeauna legătura dintre concept și practica fizică. Dorința de a te mișca este un impuls brut și, prin urmare, este modelată de interesele intelectuale și preocupările dramaturgice. În lucrările mele am dezvoltat cu dansatorii anumite sarcini, reguli și limitări care definesc în același timp structura și materialul unei piese. În ultima mea lucrare, Variations 1, căutarea structurii este o temă dominantă, în timp ce principiile de reguli și crearea acestora se transformă într-un fel de de joc dezordonat.

De-a lungul anilor, însă, am dezvoltat practici fizice în relație cu oricare spectacol la care am lucrat, cu atât mai mult cu cât lucrările mele sunt aproape întotdeauna bazate pe mișcare. Practici de mișcare anume, cum ar fi tehnica Klein de yoga etc mi-au sprijinit cercetările în mișcare de-a lungul anilor. Totuși, pentru că tind să văd corpul ca o suprafață de producție a imaginii și mă interesează schimbarea unei anumite percepții a corpului, atunci practica mea fizică se supune multor ore de improvizație care conduc la descoperirea unei anumite imagini sau percepții a corpului. Sunt întotdeauna foarte inspirată de ideea de a lucra cu necunoscutul și de ce anume ai putea descoperi în acest proces.

AC: Cum ți-ai descrie procesul de creație în general? Există vreo metodă specifică pe care ai dezvoltat-o de-a lungul anilor, ca cercetare?

CS: Singuratic într-un sens pozitiv, un proces de creație poate începe adesea cu un obiect, o imagine, un text, în general ceva cu care corpul poate crea o legătură. Uneori ideile rămân aceleași pentru câțiva ani sau chiar mai mult înainte de a le folosi. Când am început să creez, am fost foarte legată de experiența vieții de zi cu zi, de locul unde am trăit și reflecțiile mele despre politică, deși această experiență a fost mult abstractizată în contextul lucrării. La început, am petrecut ani întregi lucrând singură și fără ca cineva să vadă ce fac. A fost o perioadă extrem de importantă, pentru că am avut posibilitatea să pun bazele conceptuale pentru câteva din viitoarele mele lucrări. Acum mă întreb ce mă interesează cu adevărat și de-abia apoi continui. Mi se pare că există o progresie naturală de la spectacol la spectacol, dar nu lineară, pentru că stilul fiecărei lucrări diferă foarte mult de celelalte. Majoritatea proceselor de creație încep cu propriile cercetări personale, care pot dura luni întregi, dacă lucrez la altceva. Recent, lucrând cu grupuri, am devenit interesată de complexitate și structura coregrafică. Performerii cu care lucrez sunt din ce în ce mai instrumentali, deci este o mare schimbare. Ca metodă, am creat colaje în jurul temelor dramaturgice, folosind imagini și texte despre care am discutat și pe care le privim zilnic, astfel încât toată lumea lucrează la toate nivelurile piesei. Totuși, pe partea de interpretare rămân întotdeauna în afara lucrării, pentru că am nevoie de această perspectivă.

AC: Vei prezenta în acest an două performance-uri în programul eXplore dance festival: I not I și We are the monsters. Văd în ambele spectacole un interes direct și vizibil pentru modul în este perceput corpul; funcționalitatea fizică, dincolo de orice semnificație filosofică, care oricum survine, dar într-un mod mai subtil, lăsând spațiu imaginației. Sunt interesată de modul în care ai dezvoltat acest proces cu dansatori profesioniști (în I not I) și cum vezi lucrul cu copiii (atât ca performeri, cât și ca spectatori).

CS: În I not I am lucrat pornind de la imaginile și percepția corpului pe care am vrut să le creăm. De mai mult timp mă interesa ideea unei percepții a propriului corp ca fiind cumva “altul”, ca ceva care nu aparține sau este conectat la senzațiile interne. Astfel, corpul, sau doar o parte din el, devine din această perspectivă ca un obiect, pe măsură ce observăm și întruchipăm experiența. În spectacol, acest fenomen este personificat de un membru rătăcitor ce pare disociat de restul corpului. Lucrând cu această idee, am început cu o serie de gesturi pentru brațe pe care le-am numit “blocate”, si care produc o condiție diferită pentru corp. Poate că funcționalitatea corpului din I not I provine din faptul că această “condiție” este explorată într-un mod foarte fizic, în cum comunică și lucrează corpul în aceste conditii, mai degrabă decât într-un sens metaforic sau emoțional.

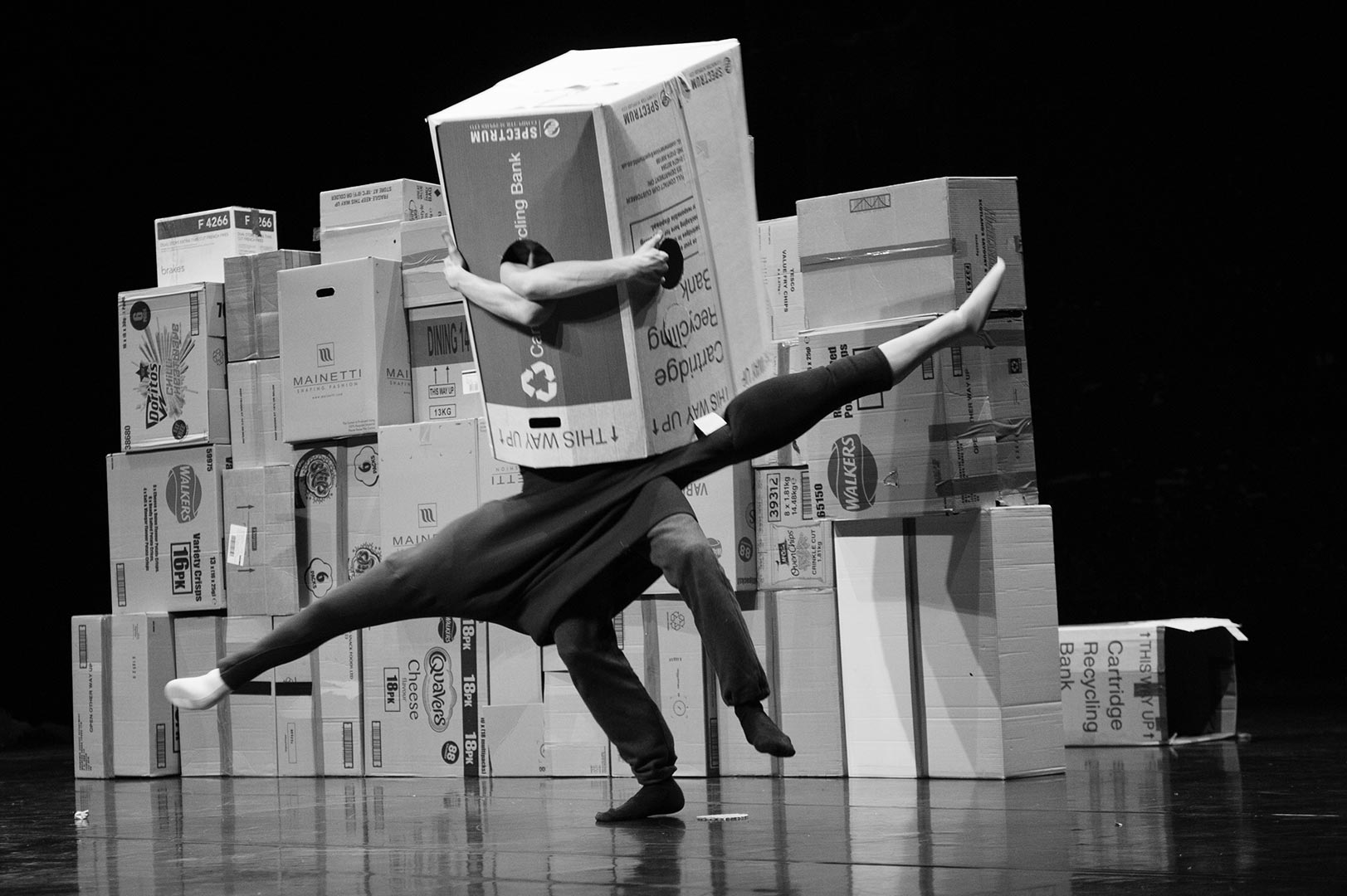

Lucrul cu copiii a început mai mult ca un mod de a deveni mai angajată politic, deși cumva într-un mod naiv, gândindu-mă la public și democratizarea accesului la dans. În 2008, am început să lucrez cu copiii și să mă gândesc la rolul și importanța imaginației în acest proces. Ideea inițială era de a oferi ateliere și performance-uri gratuite în școli și zone defavorizate din Glasgow. De atunci, proiectul s-a dezvoltat în We are the monsters, un performance de 25 de minute și un atelier. Estetica spectacolului este low-fi, aducând împreună straniul și elemente de science fiction și experiența cotidianului și a homemade-ului. În această lucrare, costumul devine un mod simplu, direct și amuzant de a crea figuri care provoacă percepția și logica fizică. Mi-a plăcut ideea ca după vizionarea spectacolului copiii să-și pună propriile haine pe dos sau cu fața la spate, să se gândească de două ori la potențialul de divertisment al unei cutii de carton și la desenarea și imaginarea unor diferite tipuri de figuri de monștri. Îmi place publicul alcătuit din copii pentru că se exprimă foarte direct; de exemplu, vorbesc în timpul reprezentațiilor, strigă comentarii, râd, vorbesc, se plictisesc etc. Nu am lucrat cu copii ca performeri în afara unui atelier, dar e de avut in vedere pentru viitor.

AC: I not I este co-produs de Southbank Centre, în cadrul proiectului european Jardin d’Europe. Cum vezi, ca artist, sistemul de producție la nivel european, metodele sale actuale și posibilele îmbunătățiri în viitor? Crezi în “puterea” rețelelor ? Dau rezultate, aduc recunoaștere internațională sau cresc posibilitatea de schimburi internaționale?

CS: Comparativ cu SUA și Asia, sistemul european este unul eficient. Încă se poate, chiar dacă din ce în ce mai greu, să realizezi, finanțezi și să faci să circule o lucrare. Mă întreb, însă, de ce se pune atât de mult accent și de ce se investește atât de mult în oportunități de rezidență și mobilitate pentru artiști. De ce trebuie artiștii să fie mobili ? Ce are de-a face asta cu producția artei? Există, bineînțeles, aspecte negative și pozitive ale rezidențelor și oportunităților de mobilitate, dar aceasta pare a fi o necesitate. Poate că stilul de viață de tip rezidențe se potrivește oamenilor de o anumită vârstă și cu un anumit stil de viață, dar nu este, în opinia mea, o soluție pe termen lung pentru artiști cu familie sau a căror muncă este realizată în studio. După mai mult de zece ani de lucru, înțeleg că lucrurile nu s-au îmbunătățit foarte mult, câtă vreme este foarte dificil să creezi structuri și orice fel de continuitate în contextul creatiei project-based. Orice fel de traiectorie pe termen lung pare să se concentreze pe propria investiție personală, deci întrebarea este cât de multă putere are un artist individual să susțina o practica în acest sistem. Este un subiect complex, dar, pe scurt, viitoarele îmbunătățiri pot include mai multe finanțări pe termen lung pentru cei care sprijină producția operelor artistice, producători independenți etc.

Văd rețelele ca o mișcare pozitivă, pentru că permite gruparea resurselor și a cooperării internaționale. Este greu să discut la nivel instituțional dacă rețelele au sau nu putere sau daca promovează schimburile, deoarece nu sunt implicată direct în politicile acestui sistem. Cu siguranță, sunt foarte bucuroasă că am beneficiat de o rezidență de co-producție Jardin d’Europe, dar în cazul meu este greu să cuantific impactul pe care aceasta l-a avut, pentru că am senzația că face parte dintr-un proces mai lung pe care îl construiesc de mulți ani în vederea prezentării și schimbului internațional.

Traducere de Cristina Niculae